From VOA Learning English, welcome to The Making of a Nation, our weekly program of American history for people learning English. I’m Steve Ember.

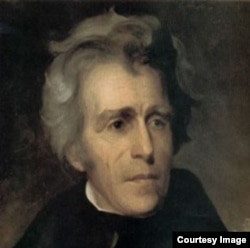

This week we continue the story of the presidency of Andrew Jackson.

Jackson took office in 1829. He was popular with many voters. They saw him as the symbol of the common man. But Jackson’s first term seemed to be mostly a political battle with his vice president, John C. Calhoun.

As his presidency went on, another struggle began. This time, it was Jackson against the Bank of the United States.

Andrew Jackson Took on the Bank of the United States

The First Bank of the United States had closed in 1811. But without a central bank, the country’s finances had suffered during the War of 1812.

So in 1816, Congress provided money to establish the Second Bank of the United States. The bank could provide loans, pay bills, collect taxes and move money around the country.

Congress gave the bank a charter to do business for 20 years. The government owned one-fifth of the bank. A small group of private citizens owned the rest. Lawmakers gave the bank enormous power.

The Bank of the United States had $35 million in capital. Some of that money came from the government. Most came from investors.

Historian Bray Hammond notes that at the time, the Bank of the United States was the richest corporation in the world.

The Bank of the United States also printed the country’s paper money. And it was the only bank permitted to have offices across the nation.

By making it easy or difficult for businesses to borrow money, the bank’s owners could control the economy in almost any part of the United States.

“What this means is that you are granting -- and Congress did grant -- exclusive privileges to the Bank of the United States, which meant exclusive money-making opportunities to its stockholders.”

Historian Daniel Feller explains that the Bank of the United States helped the government to do its business effectively and efficiently. But it also helped the people who owned stock in the bank.

During Jackson's presidency, a man named Nicholas Biddle led the Bank of the United States. Biddle was an extremely intelligent man. He had completed his studies at the University of Pennsylvania when he was only 13 years old. When he was 18, he was sent to Paris as secretary to the American minister.

During America's war with Britain in 1812, Biddle helped establish the Bank of the United States. He became its president when he was only 37 years old.

Biddle clearly understood his power as president of the Bank of the United States. In his mind, the government had no right to interfere in any way with the bank's business.

President Jackson did not agree. Nor was he very friendly toward the bank. Not many people from western states were. They did not trust the bank's paper money. They wanted to deal in gold and silver.

Jackson criticized the bank in each of his yearly messages to Congress. He said the Bank of the United States was dangerous to the liberty of the people. He said the bank could build up or pull down political parties through loans to politicians.

Jackson opposed giving the bank a new charter. He proposed that a new bank be formed as part of the Treasury Department.

Jackson Vetoed a new Charter Approved by the Senate

The president urged Congress to consider the future of the bank long before the bank's charter was to end in 1836. Then, if the charter was rejected, the bank could close its business slowly over several years. Changing the banking system slowly, Jackson said, would prevent serious economic problems for the country.

But the bank’s president wanted to renew the charter early. He made the request in January 1832 — nine months before the next presidential election.

Jackson’s opponent, Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky, was sure that the issue of the bank could win him some votes. Clay argued his case on the floor of the Senate for three days. He strongly urged the Senate to renew the bank's charter. He said the country was in the middle of a revolution, not yet a bloody revolution. But things were happening that pointed to a total change of the pure republican character of the government. Power was being centered in the hands of one man, he said. He meant President Jackson.

Clay added that if Congress did not act, the government would fail. Clay then asked the Senate to condemn Jackson, saying he violated the Constitution and the nation's laws. The Senate approved the resolution.

The chief opponent to the bank was Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri. He objected to the renewal of the charter, he told the Senate, because the bank was too great and powerful and made the rich richer and the poor poorer.

The Senate finally voted on the bank's new charter. The vote was 28 for renewal and 20 against. The House voted three weeks later. It also approved the charter, 107 to 85.

The lawmakers sent the bill to the White House. President Jackson debated it with members of his cabinet. Some wanted to negotiate a compromise. But Jackson decided to veto the bill in the strongest possible language.

On July 10, 1832, Jackson sent a message to Congress explaining his reasoning. Jackson said he did not believe the bank's charter was constitutional.

Jackson also spoke of the way the bank moved money from West to East. He said the bank was owned by a small group of rich men, mostly in the East. Some of the owners, he said, were foreigners. Much of the bank's business was done in the West. The money paid by westerners for loans went into the pockets of the eastern bankers. Jackson said this was wrong. Then the president spoke of his firm belief in the rights of the common man.

"It is to be regretted," he said, "that the rich and powerful bend the acts of the government to their own purposes."

Jackson said that instead, the government should shower its favors — as heaven does its rain — on the high and low alike, on the rich and the poor equally.

Jackson’s veto of the bank bill may have cost him votes among the wealthy, but it earned him votes among the common people, like farmers and laborers. He easily won re-election in November of 1832. Martin Van Buren became his vice president.

Historian Daniel Feller says Jackson believed his victory meant that Americans supported his policies, including the bank veto.

“He had a very popular personal image. It’s possible he would’ve been re-elected by the same margin or larger anyway. The one thing we can say looking forward is that when, later on, you had somebody carrying on Jackson’s policies absolutely faithfully, without Jackson’s personal charisma, he proved to be not nearly so popular.”

Jackson Triumphed as Biddle Blamed for Financial Panic

In his second term, Jackson stopped putting federal money into the Bank of the United States. Instead, he put the money into state banks.

The bank president, Nicholas Biddle, fought with all his power to keep the bank open. He demanded that borrowers immediately repay their loans. Businesses struggled without the bank's assistance. Workers lost their jobs.

Biddle blamed President Jackson for the financial panic. And critics of Jackson’s bank policy called him “King Andrew the First.” But as time passed, business people began to see that the Bank of the United States was being much tighter in its money policy than was necessary. They began to feel that it was the bank’s president — not Jackson — who was responsible for the serious economic situation in the country.

Biddle took no responsibility for the financial crisis.

He then made a very bad decision. Biddle asked the governor of Pennsylvania to make a speech supporting the bank. At the same time, Biddle refused to lend the state of Pennsylvania $300,000.

The governor was furious. Instead of making a speech supporting the bank, he made one that sharply criticized it.

Two days later, the governor of New York proposed that the state sell $4 or $5 million of stock for loans to help state banks. The New York legislature approved selling even more.

Strengthening state banks helped break the power of the Bank of the United States. Nicholas Biddle began to see that the battle was lost. He started making more loans to businesses. The economic panic slowly ended.

Jackson's victory over the Bank of the United States was clear. Biddle started to lose the support of many members of Congress. In the House of Representatives, James Polk proposed four resolutions about the bank. One said the bank should not get a new charter in 1836.

The second resolution said government money should not be deposited in the bank.The third said the government should continue to put its money in state banks. And the fourth proposed an investigation of the bank and the reasons for the economic panic in the country. All four of these anti-bank resolutions were approved.

One of Biddle's aides described the feelings of bank officials. This day, he said, should be ripped from the history of the republic. He said the president of the United States had seized the public treasury and the representatives of the people had approved it.

Jackson won what he himself considered a glorious triumph.

Another major event in Jackson’s second term was the situation in Texas. The struggle over Texas and the Battle of the Alamo will be our story next week.

I’m Steve Ember, inviting you to join us next time for The Making of a Nation — American history from VOA Learning English.