From VOA Learning English, welcome to The Making of a Nation, our weekly program about American history for people learning English. I’m Steve Ember.

Andrew Jackson was nearing the end of his presidency. He had served two terms. For many Americans, Jackson remained incredibly popular. They liked that a poor boy from the frontier who could barely read and write grew up to become president.

Historian Daniel Feller is an expert on Andrew Jackson. He calls the president and war hero the ultimate American self-made man.

“He’s a quintessentially American figure. You can’t imagine anybody like this getting to be the head of a country at that time, certainly anywhere else but in the United States. And even in the United States it would’ve been unheard of just a few years before.”

Daniel Feller says Jackson often used government to help ordinary people instead of the rich and powerful. For this reason, many called him the “people’s president.”

Differing views on Jackson...

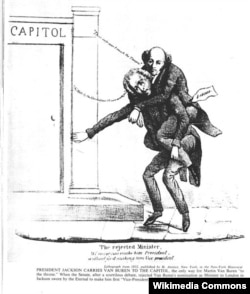

But not everyone agreed. His opponents said tyrants have always spoken in the name of the people. They said Jackson used his popularity to do whatever he wanted, whether it was legal or not. His opponents in Congress even denounced him with a censure resolution for not releasing some of his papers to the government. They called him “King Andrew.”

Many American Indians called Jackson yet another name. They called him “Jackson the Devil.”

Jackson wanted Native Americans in southern states, including Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and Tennessee, to move west. Jackson did not think it was right for Indian tribes to exist as independent nations within the United States. And white voters wanted Indians’ land for farming.

Historian Daniel Feller points out that the United States government had tried to get Indians to move away from white settlements for a long time – long before Jackson became president.

“But Jackson brought an urgency to it that none of his predecessors had. [Former presidents John] Quincy Adams and [James] Monroe had endeavored to remove Indians when Indians seemed to be willing to be removed. Jackson took the position that they needed to be removed now.”

In 1830, Jackson pushed a bill through Congress called the Indian Removal Act. The bill allowed him to create new Indian homelands in the Oklahoma territory, an area west of the Mississippi River where few white Americans lived at the time. The federal government would essentially trade the Indians their old land for the new land, and pay for tribes to move west permanently.

“He managed to convince himself, and I think that’s the best way to put it, that he was actually doing the Indians a favor. That Indian tribes that remained in proximity to whites simply disintegrated. Their tribal structure, their national structure, disintegrated. They died.”

Daniel Feller says just because Jackson believed he was helping the Indians did not mean he did not benefit from their removal, or that he was right.

Besides, the Indians did not have much choice. Jackson told them that if they did not accept his offer, their nations would be controlled by the American government.

The Chickasaw, Choctaw and Creeks agreed under pressure. The Cherokees resisted. They even took their case to the Supreme Court, which agreed that the Indians were independent from state authority.

But Jackson and the state of Georgia ignored the Supreme Court’s decision. Eventually, soldiers forced the Cherokees from their homes and marched them over 1,600 kilometers to Oklahoma. More than 5,000 died. The forced march later became known as the Trail of Tears.

Even the Indians who survived continued to suffer. The United States government did not meet the terms of the treaty. Few Indians were paid for their goods. Most were not given food and other supplies during the journey or when they arrived in Oklahoma.

Daniel Feller notes that the United States has a long history of defaulting on its treaties with Indian nations, both before and after Andrew Jackson. Andrew Jackson might not have intended for the Indians to suffer so much, but he did not lead his government to respect and protect them either.

“There are many who regard Jackson as being the kind of epitome, the exemplar, the personification, of everything that has been wrong, not only regrettable but perhaps evil in white America’s treatment of the Indians.”

Daniel Feller says Jackson’s treatment of the Native Americans, along with some of his other actions, complicates his image as an American hero.

“If you look at Jackson’s own personal rise, it’s a pretty impressive rise. It leaves a lot of dead people, and a lot of displaced or abused populations behind it, including Indians, including slaves, including personally the people he shot. So again it’s a complicated image. It shows this American character in both you might say its best and its most disturbing light at the same time.”

Jackson supports Van Buren for next President

In 1836, the American public voted for their next president. Andrew Jackson had served for eight years. He did not want another term. He supported his vice president, Martin Van Buren.

Van Buren had been very close to the outgoing president.

In the election of 1828, Van Buren had been successful in forming a strong political alliance. This alliance helped put Jackson in the White House. Jackson was grateful for Van Buren's help, and asked him to come to Washington to serve as secretary of state.

Van Buren quickly became the most powerful man in Jackson's cabinet. He was able to help Jackson in negotiations with Britain and France. But his greatest help was in building a strong political party for Jackson.

Van Buren built up the Democratic Party by removing people from government jobs if they had not supported Jackson. These jobs were then given to those who had supported the president. Ultimately, it was the Democratic Party that gave Jackson wide support for his policies.

Van Buren served as Jackson’s secretary of state for two years.

By this time, Jackson had decided that Van Buren would be the best man to follow him as president. Jackson offered to resign after the 1832 elections and give Van Buren the job of president.

Van Buren rejected the offer. He said he wanted to be elected by the people. But he agreed to be Jackson's vice president in 1832.

Four years later, at Jackson's request, the Democrats chose Van Buren to be their presidential candidate. Several candidates from the newly formed Whig Party opposed him. But the Whigs were divided, and Van Buren easily won the election.

March 4, 1837, was a bright, cold day. The winter sun shone over the crowd that had gathered in Washington to watch the swearing-in of the new president.

Andrew Jackson left the White House in the presidential carriage, riding beside Martin Van Buren. It was the first time a president and a president-elect rode to the Capitol together for the inauguration.

The big crowd on the east side of the Capitol grew quiet when Jackson and Van Buren walked up the steps of the building. After Chief Justice Roger Taney swore in President Van Buren, the new president gave his inaugural speech.

Then Andrew Jackson started slowly down the steps. A mighty cheer burst from the crowd.

"For once," wrote Senator Thomas Hart Benton, an ally of Jackson, "the rising sun was eclipsed by the setting sun."

The day after Van Buren became president, Jackson met with a few of his friends. Frank Blair, the editor of Jackson's newspaper, was one of them. Senator Benton was another. It was a warm, friendly meeting. They thought back over Jackson's years in the White House and talked about what had been done.

Jackson said he thought his best piece of work was getting rid of the Bank of the United States. He said he had saved the people from a monopoly of a few rich men.

Someone asked about Texas. Jackson said he was not worried about Texas. That problem would solve itself, he said.

Regrets?

Did he have any regrets about anything? "Only two," said Jackson. "I regret I was unable to shoot Henry Clay or to hang John C. Calhoun."

The next morning, March 6, Jackson left Washington to return to his home in Tennessee.

Jackson was to leave the capital by train. Thousands of people lined the streets to the train station, waiting for a last look at their president. Jackson stood in the open air on the rear platform of the train. His hat was off, and the wind blew through his long white hair.

The locomotive bell rang. There was a hiss of steam. And the train began to move. Jackson bowed. One man who was there said it was as if a bright star had gone out of the sky.

Jackson lived for eight more years. He read as many as 20 different newspapers, exchanged letters with many people in government and spent time with his son and grandchildren. But Jackson’s health had never been very good. He had been shot many years before, and the gunshot wounds created problems.

Andrew Jackson died at home on June 8, 1845. He was 78 years old.

Back in Washington, Martin Van Buren continued Jackson’s legacy by carrying out many of his policies. Van Buren and his government will be our story next week.

I’m Steve Ember, inviting you to join us next time for The Making of a Nation — American history from VOA Learning English.