STEVE EMBER: I’m Steve Ember.

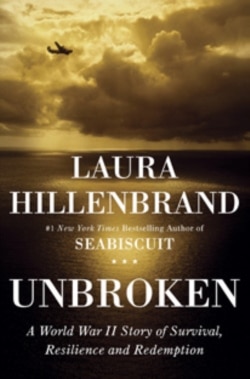

BARBARA KLEIN: And I’m Barbara Klein with the VOA Special English program EXPLORATIONS. Today we discuss the best-selling book “Unbroken,” by writer Laura Hillenbrand. It is a story about survival, heroism, and the strength of the human spirit in overcoming hardship.

(SOUND)

JIM TEDDER: All he could see, in every direction, was water. It was June 23, 1943. Somewhere on the endless expanse of the Pacific Ocean, Army Air Forces bombardier and Olympic runner Louie Zamperini lay across a small raft, drifting westward. Slumped alongside him was a sergeant, one of his plane’s gunners. On a separate raft, tethered to the first, lay another crewman, a gash zigzagging across his forehead. Their bodies, burned by the sun and stained yellow from the raft dye, had winnowed down to skeletons. Sharks glided in lazy loops around them, dragging their backs along the rafts, waiting.

The men had been adrift for twenty seven days. Borne by an equatorial current, they had floated at least one thousand miles, deep into Japanese-controlled waters. The rafts were beginning to deteriorate into jelly, and gave off a sour, burning odor. The men’s bodies were pocked with salt sores, and their lips were so swollen that they pressed into their nostrils and chins. They spent their days with their eyes fixed on the sky, singing “White Christmas”, muttering about food. No one was even looking for them anymore. They were alone on sixty-four million square miles of ocean.

A month earlier, twenty-six year old Zamperini had been one of the greatest runners in the world, expected by many to be the first to break the four-minute mile, one of the most celebrated barriers in sport. Now his Olympian’s body had wasted to less than one hundred pounds and his famous legs could no longer lift him. Almost everyone outside of his family had given him up for dead.

STEVE EMBER: Those lines were from Laura Hillenbrand’s book “Unbroken.” The book opens by telling about Louis Zamperini and his memories of growing up in southern California during the nineteen twenties and thirties. His parents were immigrants from Italy. Louie Zamperini was a big troublemaker as a child and young adult.

He would get into fights, steal things, and play jokes on people. But he became a big success when he directed that rebellious and independent spirit into sports. He became an excellent runner who set records. He even competed in the nineteen thirty-six Olympics in Berlin, Germany.

BARBARA KLEIN: After the United States entered World War Two, Louie Zamperini served in the Army Air Forces on dangerous operations in the South Pacific. He was a member of a crew that flew a B-24 warplane. These heavy bombers were known for being difficult to fly and control. Mr. Zamperini was responsible for working with the navigator to make sure bombs dropped from the plane hit their targets.

Laura Hillenbrand’s writing is so detailed that the reader feels he or she is part of the story. She gives a detailed explanation of air operations during the war and their huge risks. Ms. Hillenbrand says American soldiers did not only die in battle. She says over thirty-five thousand airmen died in non-battle situations, mostly accidental crashes. She also discusses military technology, air battles, and American and Japanese war efforts.

STEVE EMBER: In May of nineteen forty-three, Louie Zamperini and his crew left their base in Hawaii to begin a rescue operation. But their plane crashed into the Pacific. Of the eleven crew members, only Mr. Zamperini and two others survived the crash. The men used small rafts from the plane to float on the water. But they have almost no equipment with which to survive the heat, hunger, thirst, storms and shark attacks they would face. They developed unusual ways to capture rainwater to drink, and fish and birds to eat. They also created mental exercises so their minds will stay sharp.

BARBARA KLEIN: One day the men saw an airplane, and signaled for it to find them. But it was a military plane from Japan, America’s enemy during the war. The plane passed overhead two times and fired bullets at them. The men jumped in the water, which was filled with sharks. They were not harmed, but one man later died from lack of food.

Louie Zamperini and pilot Russell Allen Phillips survived forty-seven days at sea before their raft washed up on an island. They were then captured by the Japanese military. They became prisoners of war, and were separated.

STEVE EMBER: In many ways, conditions in Japanese prisoner camps during the war were worse than at sea. Mr. Zamperini and other prisoners faced torture and mental abuse. They also received little food, water or medical care.

Laura Hillenbrand says the biggest problem for prisoners of war during this period was not physical pain or food shortages. It was the loss of dignity, self-respect and honor. To keep their dignity, prisoners would fight back in whatever small way they could. They would secretly steal supplies and newspapers to learn of news about the war. They would use signals to communicate with each other, although they were barred from speaking. Some would make paper and attempt to keep notes of their experiences.

LAURA HILLENBRAND: “Louie’s life is a lesson in perseverance. Louie never gave up on the idea that he could get through what he was going through, which is quite extraordinary given how far into extremity he went over his journey. And the thing that is so inspiring about him is that he didn’t give that up. And, his life became a demonstration of how far a resilient will could carry a man even when every other aspect of the world was against him.”

BARBARA KLEIN: The book “Unbroken” is not just the story of Louie Zamperini. It also explores the nature of human survival in general. It tells how some people can survive the most impossible situations imaginable. The book describes some of the terrible effects of war. And it honors the many Allied soldiers and prisoners of war who lived through World War Two, and those that never came home.

(MUSIC)

STEVE EMBER: Louie Zamperini was in prison for over two years, until the war ended in nineteen forty-five. While the American military believed him to be dead, his family never gave up hope that he had survived. But his struggles did not end with the war. After returning home, Mr. Zamperini faced great emotional pain from the stress of his experiences, as many soldiers did after the war. He drank too much alcohol. His behavior nearly destroyed his marriage. He was filled with hatred and anger for his captors.

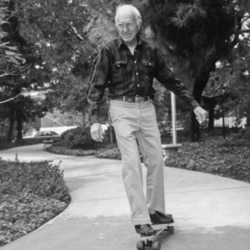

But in time, he found help with religion. He found work teaching troubled boys about sports and the outdoors. And, he came to accept his past and offer forgiveness to his captors. Louie Zamperini has spent much of his life traveling. He talks about his experiences so his story can help others.

BARBARA KLEIN: Laura Hillenbrand spent seven years researching and writing her book. She studied personal letters, photographs, historical documents and books, and prisoner of war descriptions. She talked with many witnesses, both Japanese and American, who survived the war.

She also spent countless hours talking by telephone to Louie Zamperini. Yet she has never met the subject of her book in person because she cannot travel. Ms. Hillenbrand has suffered from extreme chronic fatigue syndrome since she was in college. Because of her condition, she rarely leaves her home in Washington D.C.

STEVE EMBER: Ms. Hillenbrand has told reporters that she likes to write about subjects that let her mentally climb out of her own body. She says she has a sickness she cannot defeat. That is why she is interested in how others face hardship. She chooses subjects who overcome great suffering and learn to face the emotional side of those difficulties. She says athletes are defined by this struggle to overcome difficulty.

Ms. Hillenbrand’s first book, “Seabiscuit,” was about a struggling racehorse that became a great champion and national hero. It was while she was researching this book that she discovered Mr. Zamperini. He and Seabiscuit were both famous during the nineteen thirties for their racing speed.

BARBARA KLEIN: Louie Zamperini is now ninety-four years old, and in great health and spirits. He told a reporter that when he first read “Unbroken,” he had to keep looking out of the window of his California home. Mr. Zamperini did this to remind himself that he was not back in the prisoner camp. He says Ms. Hillenbrand has brought his soldier friends back to life. And, he says that because she herself has suffered so much, she was well equipped to put their suffering into words.

(MUSIC)

STEVE EMBER: This program was written and produced by Dana Demange. I’m Steve Ember.

BARBARA KLEIN:

And I’m Barbara Klein. Our reader was Jim Tedder. Join us again next week for another EXPLORATIONS program on the Voice of America.