From VOA Learning English, welcome to The Making of a Nation, our weekly program of American history for people learning American English. I’m Steve Ember in Washington.

James K. Polk moved into the White House after his swearing-in as the nation's 11th president on March 4, 1845.

Polk told voters during the election campaign he would serve only one term as president. During those four years, he wanted to achieve -- or reach -- four main goals. Two of his goals related to money. Polk wanted to reduce taxes on imports, and to establish an independent treasury.

His other goals related to expanding the country to the Pacific Ocean. President Polk wanted to secure the Oregon Territory and California for the United States.

Polk Believes U.S. Should Extend from Atlantic to Pacific

Those who supported the president shared Polk’s belief that the United States should extend from sea to sea — from the Atlantic to the Pacific. They felt it was God's will, and their duty, to spread American democracy and freedom across the continent. In the words of poet Walt Whitman,

"It is for the interest of mankind that [America's] power and territory should be extended -- the farther, the better."

One way Americans wanted to extend the country was by making the Oregon Territory part of the United States. The territory included what are now the U.S. states of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, as well as part of the Canadian province of British Columbia.

American traders established claims to the Oregon territory early in the country’s history. But British explorers gave Britain claims to the same territory. The two countries could not agree on how to divide Oregon between them. Since few white settlers lived in Oregon, Britain and the United States agreed to occupy the area jointly.

This joint occupation worked well until the 1840s. Then, thousands of Americans began moving west to Oregon. The new settlers wanted all of Oregon to belong to the United States.

President Polk agreed. He thought the United States had strong claims to the entire territory. But he said he would compromise. He offered to divide Oregon at the 49th parallel of latitude. Everything north of this line would belong to Britain. Everything south of it -- including the Columbia River -- would belong to the United States.

Britain's minister in Washington rejected the offer. He said Britain would accept nothing but the Columbia River as the southern border of British Oregon.

President Polk said America had no choice then but to claim all of Oregon. He seemed to say the United States would fight, if necessary, to defend its claim.

Polk did not really want war. But he thought he needed a strong position to negotiate with Britain.

In London, the British government decided Oregon was not worth a war with the United States. After all, Britain had moved its trading center on the Columbia River north to Vancouver Island. So there was no real reason to demand rights to the use of the river.

The British foreign minister proposed a treaty that would divide the territory at the 49th parallel of latitude. The proposal was almost the same that President Polk had made earlier.

Treaty Makes 49th Parallel Northern U.S. Border

The United States accepted the proposal. The treaty made the 49th parallel the U.S. border from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean. South of this was California.

An American government minister once described California as the richest, the most beautiful, and the healthiest country in the world. The official said the port of San Francisco was big enough to hold all the navies of the world. He said someday San Francisco would control the trade of all of the Pacific Ocean.

There was only one problem.

“It was owned by Mexico.”

Historian Robert Merry wrote a book about James K. Polk. Mr. Merry says Polk wanted to bring California into the union anyway.

“So obviously he had some underlying ideas about how that might be done.”

At first, the United States attempted to buy California from the Mexican government. But Mexican officials refused even to talk about selling California to the United States. When the U.S. Congress approved statehood for Texas in early 1845, Mexico broke relations with the United States all together.

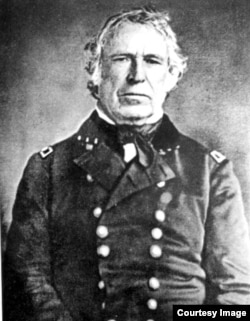

President Polk ordered the commander of the U.S. Army in Texas, Zachary Taylor, to move his forces into the disputed area near the Rio Grande River. The river formed part of the border between Texas and Mexico.

Polk sent a representative to Mexico in an effort to re-establish diplomatic relations. But the Mexican government refused to talk with the diplomat.

General Taylor sent one of his officers across the Rio Grande to meet with Mexican officials. The Mexicans protested. They said the area across the river was Mexican territory. The movement of American troops there, they said, was an act of war.

For almost a month, the Americans and the Mexicans kept their positions. Then, on April 25, 1846, General Taylor received word that a large Mexican force had crossed the border a few kilometers up the river. A small force of American soldiers went to investigate. They were attacked.

All of the Americans were killed, wounded, or captured. General Taylor quickly sent a message to President Polk in Washington. It said war had begun.

Taylor’s message arrived at the White House on May 9. A few days later, the president asked Congress to give him everything he needed to win the war and bring peace to the area. Some members of Congress did not want to declare war against Mexico. They believed the United States was responsible for the situation along the Rio Grande. They were out-voted.

Later, Polk wrote:

"We had not gone to war for conquest. But it was clear that in making peace we would, if possible, get California and other parts of Mexico."

War declared with Mexico

Many Americans opposed what they called "Mr. Polk's war." Whig Party members and anti-slavery Abolitionists in northern states believed that slave-owners and southerners in Polk's administration had planned the war. They believed the South wanted to win Mexican territory for the purpose of spreading and strengthening slavery.

The president was troubled by this opposition. But he did not think the war would last long. He thought the United States could quickly force Mexico to sell him the territory he wanted.

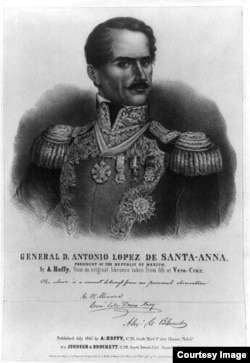

So, Polk secretly sent a representative to the former Mexican dictator Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna. Santa Anna was living in exile in Cuba. The representative said the United States wanted to buy California and some other Mexican territory. Santa Anna said he would agree to the sale, if the United States would help him return to power.

President Polk accepted the deal. He ordered the United States Navy to let the former dictator sail to the Mexican port of Vera Cruz.

But once Santa Anna returned, he failed to honor his promises. He refused to end the war and sell California. Instead, Santa Anna organized an army to fight the United States.

In four months, he built an army of 20,000 men. When General Taylor learned that Santa Anna was preparing to attack, he moved his forces to fight the Mexicans.

Taylor Commands U.S. forces: 'Tell [Santa Anna] to go to hell'

Santa Anna sent a representative to meet with General Taylor. The representative said the Americans had one hour to surrender. Taylor's answer to Santa Anna was short: "Tell him to go to hell."

The battle between the United States and Santa Anna’s army lasted two days. Losses were heavy on both sides. On the second night, the Mexican forces withdrew from the battlefield. Taylor had won.

The victory strengthened Taylor’s public image. He had already won the battle of Monterrey, a major trading and transportation center in northeast Mexico.

Other American forces also were victorious. General Winfield Scott captured the port of Vera Cruz and was ready to attack Mexico City. Commodore Robert Stockton invaded California and had raised the American flag over the territory.

Stephen Kearny seized Santa Fe, the capital of New Mexico, without firing a shot.

Still, the war was not over. President Polk's "short" war already had lasted for more than a year. Polk decided to send a special diplomatic representative to Mexico. He asked the diplomat to negotiate a peace treaty whenever Mexico wanted to stop fighting.

A ceasefire was declared. But attempts to negotiate a peace treaty failed. Santa Anna used the time to prepare for more fighting. So General Scott ended the ceasefire. His men began their attack on Mexico City.

The fighting lasted one week. Finally, the government of Mexico surrendered and Santa Anna left power.

US, Mexico Sign Peace Treaty

On February 2, 1848, the United States and Mexico signed a peace treaty. Mexico agreed to give up California and New Mexico. And, Mexico would recognize the Rio Grande as the southern border of Texas. The war was officially over.

But historian Robert Merry says President Polk suffered because of the conflict. The war with Mexico, Merry says,

“Ended up being a much longer war than he had anticipated and much more costly in terms of lives, in terms of money, and in terms of his political standing.”

The war with Mexico also influenced the US election in 1848. That election, and the problem of what to do with the new territories, will be our story next week.

I’m Steve Ember inviting you to join us next time for The Making of a Nation – American history from VOA Learning English.