The United States is home to 562 federally recognized American Indian Nations, each with its own language.

Yet the number of Native Americans with the ability to speak their tribe’s language has decreased over the past century.

Now, Indian Nations are trying different ways to expand the number of native speakers, and increase interest in their communities to learn tribal languages.

Language in the United States

Since the late 1800s, many American Indian children have attended boarding schools. At the time, Indian children were required to attend schools by law, and the federal government forced Indian families to send their children to such schools.

The purpose of this requirement was to educate young people, as well as assimilate them in “American ways of life.”

The children were separated from their families, and given English names. As many boarding schools were operated by religious groups, the children were also taught Christianity.

One of the most lasting effects of these schools was language. The teachers often taught Native American students in English, instead of the language of their parents.

AnCita Benally serves as education program manager for the Navajo Nation. She says the boarding school students were told they needed to learn English in order to get a job, earn money and buy a house or nice things.

Benally says the effect of these schools has lasted for generations. When the “boarding school generation” started having children, they were only taught English. At the time, many people believed this made sense – for economic and other reasons. But a lot of Native Americans could no longer speak their tribal language well enough to pass it on to their children.

Today, even though tribal-run schools exist on their territory, most tribes report that their youngest members have trouble speaking traditional, tribal languages. Fearing a loss of history and culture, the Indian Nations are experimenting with new ways to increase the language ability and interest of tribal members.

Looking to Technology

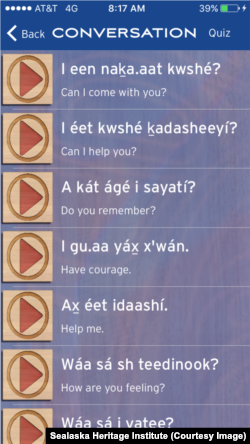

At least one organization is turning to modern technology. The Sealaska Heritage Institute, a nonprofit group, has developed a podcast and two apps for speakers of the Tlingit language.

The Tlingit tribe has about 10,000 members. They live mainly in southeastern Alaska. But as of 2013, the tribe had only 125 native speakers left. This is low, considering that every other tribe in Alaska has a higher percentage of native speakers. In addition, very few young people are able to speak Tlingit.

“All first language fluent speakers are over the age of 60,” noted Katrina Hotch, Education Program Coordinator at Sealaska Heritage Institute. She added “There are really advanced younger learners, but it’s still an urgent need.”

Hotch said the apps and podcast were created so that schools could establish sensitive cultural and language environments for Tlingit students in their classrooms.

Currently, there are two apps, called “Learning Tlingit,” and “Tlingit Language Games.” The Learning Tlingit app serves as a language guide. It provides Tlingit words and expressions, the tribal alphabet, as well as a basic list of the words included.

With the “Tlingit Language Games” app, users are given a choice of different places or environments, like a house, forest or ocean. Users choose different images and hear the word for each object spoken. They can then take a simple test on the words they learned.

In addition, Hotch developed a podcast, which includes both audio and video images. Each program deals with a specific subject, such as Tlingit songs, numbers, terms, and how to say difficult letters in the language.

The voices used in the apps are all from native speakers. Hotch says the biggest problem facing learners of the language is getting access to Tlingit speakers.

Changes in the classroom

Along with using technology, some tribes are training teachers and developing goals in education in order to improve their language programs.

The Choctaw are an American Indian tribe native to the southeastern United States. Roseanna Thompson is the Choctaw language and cultural integration director for the tribe’s schools in Mississippi.

Thompson told VOA that about 75% of Choctaw Indians who are teenagers or older can speak the tribal language. But only 15% of Choctaw children have that ability.

Thompson said tribal leaders decided they wanted to create language classes for elementary school students. Those schools have now set up a Choctaw language program for students through 3rd grade. This is the first time they have offered Choctaw language classes for elementary students. They also offer speaking assessment and pre-assessment testing.

Before launching the classes, Thompson and other Choctaw teachers attended a training program in how to teach native languages. They then worked with other teachers to establish their own goals for language learning.

The program is trying to reproduce how tribal members used to learn Choctaw -- through speaking. Thompson said the students first learn about spoken interactions and exchanges, before they turn to writing and grammar rules. She felt that if they focus on grammar too early, it could slow down the learning process.

Similar to the struggles with Tlingit language, Thompson says, the biggest difficulty with teaching Choctaw is “overcoming the language barrier that exists between the children, parents, grandparents, and the general public.” She adds “They may learn the language, but they can’t use it anywhere else. It is hard on our children, as well.”

Uniting with standards

Another Tribe working with educational standards are the Navajo Indians (also known as “Diné”), a tribe in the southwestern U.S.

The Navajo have the largest number of speakers of all the American Indian tribes -- with an estimated 166,826 speakers of Navajo (out of 286,731 Navajo members), according to the U.S government.

However, like most Indian tribes, many of the speakers are older adults. Few young people are learning the Navajo language. One recent study found that 53 percent of Navajo families speak only English at home.

AnCita Benally works for the Department of Diné Education, an office known as DoDE. It was part of a large project to establish standards for Navajo education. Benally says the DoDE used those rules to develop assessment tests for Navajo schools.

She warns that improving the standards for language teaching in schools is not enough. While many adult tribal members continue to speak Navajo, many younger members do not have that ability.

“The situation is becoming such that they….will be depending on the school to teach their home language. But we’re telling them it really belongs in the home and is much easier to teach them at home,” Benally said. The real step, she says, to increasing young speakers is to convince parents and grandparents that it is important to be speaking Navajo with their children or grandchildren.

“Their language is in danger and it’s up to them to keep it from disappearing,” Benally says.

I’m Phil Dierking.

And I’m Jill Robbins

Phil Dierking wrote this story for VOA Learning English. George Grow was the editor.

We want to hear from you. Write to us in the Comments Section or on our Facebook page.

_______________________________________________________________

Words in This Story

access - n. a way of getting near, at, or to something or someone

alphabet - n. the letters of a language arranged in their usual order

app - n. a computer program that performs a special function

fluent - adj. able to speak a language easily and very well

assimilate - v. to fully become part of a different society, country, etc.

integration - n. the act or condition of combining (two or more things) to form or create something

assessment - n. the act of making a judgment about something

boarding (school) - adj. a type of school where students can live during the school term

curriculum - n. the courses that are taught by a school, college, etc.

episode - n. an event or a short period of time that is important or unusual

podcast - n. a program (such as a music or news program) that is like a radio or television show but that is downloaded over the Internet

convince - v. to cause (someone) to agree to do something

grammar - n. the set of rules that explain how words are used in a language