Malaysia’s political problems have increased in the last two years although hopes were high in 2018 that the country was making democratic gains.

In 2018, a new political coalition defeated the United Malays National Organization that had ruled the country for more than 50 years. That year, a former prime minister was arrested in one of the world’s biggest cases of graft. And the nation rejected costly development projects pushed by China through its Belt and Road program. The program promises big loans to countries for development and infrastructure projects they may not be able to pay for.

But now, almost two years after the historic election, much has changed.

The United Malays National Organization is back its power. The former prime minister, Najib Razak, is still facing trial for corruption. And, the canceled Malay-China projects appear to be moving forward.

In addition, human rights activists say the country is using the coronavirus crisis as an excuse for authoritarian controls.

Reporters and other citizens have been arrested for criticizing how the country has dealt with the health crisis. Malaysia also has arrested thousands of people for violating stay-at-home orders. The country has the highest rate of such arrests in Southeast Asia outside of The Philippines.

'Democracy is dead’

Phil Robertson is the deputy Asia director at Human Rights Watch. He told VOA that “Malaysian authorities have returned to rights-abusing.”

For some, the country is going in the opposite direction of the hope for democracy brought on by the 2018 vote. That election surprised observers around the world. Hopes were high for Malaysia because, at the time, the group Freedom House worried there had been a “retreat” from democracy. Freedom House is a U.S.-supported organization that pushes for democracy and human rights.

In 2018, Freedom House even called Malaysia a good example of democracy to the world. Mahathir Mohamad, who had been prime minister before, regained the position in that 2018 vote.

But he lost this leadership again in a power struggle in March. Since then, he has criticized of the government that ousted him.

“Democracy is dead,” he wrote last month on his blog. “The whole world is laughing at Malaysia.”

He continued, saying the world called Malaysia a kleptocracy when Najib was prime minister. “But now the kleptocrats are back.”

One-day parliament

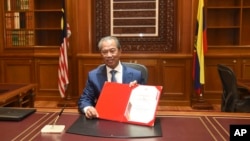

Mahathir also said that “Parliament is being silenced.” The lawmaking body has met for only one day this year. In May new Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin stopped attempts by the new government to hold a vote of confidence.

Instead, critics said he used the coronavirus crisis to bring together Parliament on May 18 for a speech by the king. He then put off any additional meetings until July. This led to questions about the administration’s aims.

Muhyiddin’s political party is the United Malays National Organization, or UMNO. His rise to the nation’s top office in March marked a return of the old ruling party.

Joel Simon is the executive director of the Committee to Protect Journalists. In April, he wrote Muhyuddin a letter requesting that he improve the UMNO’s relations with the media. He also “strongly” urged the Malay government not to bring back a law that made “fake news” a crime.

The law was supposed to stop misinformation but risked quieting critics in newspapers and on social media. Human Rights Watch said Malaysia has begun to detain or question critics on social media, opposition politicians and members of civil society.

I’m Alice Bryant.

VOA News reported this story. Alice Bryant adapted it for Learning English. Mario Ritter, Jr. was the editor.

________________________________________________________________

Words in This Story

graft –n. taking advantage of your political position or government job by taking money or property in dishonest or fraudulent ways

infrastructure –n. the basic equipment and structures (such as roads and bridges) that are needed for a country or region to function properly

authoritarian –adj. enforcing or pushing for strict obedience to authority at the expense of personal freedom

retreat –n. the act or process of moving away from something

kleptocracy –n. government by those who seek chiefly status and personal gain at the expense of the governed

vote of confidence –n. a vote showing that a majority continues to support the policy of a leader or governing body.

fake –adj. meant to look real or genuine but not real or genuine