Muqadas Ashraf was 16 years old when her parents forced her to marry a Chinese man who had come to Pakistan looking for a wife. Less than five months later, Muqadas is back in her home country and pregnant. She is seeking a divorce from a husband she says was abusive.

Muqadas is one of hundreds of poor Christian girls trafficked to China. The market for wives has grown quickly in Pakistan since late last year, activists say. Sometimes, Christian clergy members help the traffickers in exchange for money. The clergy will find very poor parents and promise them wealth in return for their daughters.

Parents receive several thousand dollars. They are told that their new sons-in-law are wealthy Chinese Christians. But most of the men are neither wealthy nor Christian. That information comes from several brides, their parents, an activist, church leaders and government officials, all of whom spoke to reporters with The Associated Press.

Most girls do not agree to the marriages. Instead, they are forced into them. Once the girls arrive in China, they find themselves alone in rural areas. They may face abuse and be left without any way to communicate with family back home or the Chinese around them.

'Greed is really responsible...'

Ijaz Alam Augustine is the human rights and minorities minister in Pakistan’s Punjab province. He told the AP, “This is human smuggling. Greed is really responsible for these marriages ... I have met with some of these girls and they are very poor.”

Augustine accused the Chinese government and its embassy in Pakistan of ignoring the situation. He says they issue visas and other travel documents without asking questions. The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs denied the accusation. It said China has zero acceptance of illegal marriage agencies.

Human Rights Watch called on China and Pakistan to take action to end trafficking. It warned in an April 26 statement of “increasing evidence that Pakistani women and girls are at risk of sexual slavery in China.”

This week, Pakistan’s Federal Investigation Agency took action. It arrested eight Chinese nationals and four Pakistanis in raids in Punjab province in connection with trafficking, Pakistan’s Geo TV reported. The agency said the raids followed a secret operation.

The Chinese embassy said last month that China is cooperating with Pakistan to act against illegal trafficking centers. Officials said, “both Chinese and Pakistani youths are victims of these illegal agents.”

Supply and demand

Saleem Iqbal is a Pakistani Christian activist and a reporter with a small Christian station, Isaac TV. He said he first began to see increased numbers of Pakistani-Chinese marriages in October. Since then, an estimated 750 to 1,000 Pakistani girls have been married to Chinese men, he said.

Pakistan’s small Christian community, centered in Punjab province, is an easy target. There are about 2.5 million Christians in the country’s majority Muslim population of 200 million. Christians are among Pakistan’s poorest people. They also have little political or social support.

Parents in Pakistan often choose husbands for their daughters. A girl’s family must pay a dowry for her to marry. They also have to pay for the wedding celebration. Pakistani husbands and their families often mistreat new wives if their dowries are considered a small amount.

But, it is different for marriages to Chinese men. The girls’ parents are given money, and the men pay all costs connected to getting married.

Some of the men seeking wives are from among tens of thousands of Chinese workers living in Pakistan. They work on projects connected to China’s Belt and Road Initiative. This effort has strengthened ties between the two countries in recent years.

Other men search directly for Pakistani wives from China. They present themselves as Christians, but church leaders involved in the deals do not ask for any proof of this.

They pay on average $3,500 to $5,000, including payments to parents, church leaders and a dealer, said Iqbal. Iqbal has taken legal action in court to stop such marriages. He has also given shelter to runaway wives, some as young as 13.

Muqadas’ mother, Nasreen, said she was promised about $5,000. She says she received nothing, however.

“I really believed I was giving her a chance at a better life and also a better life for us,” Nasreen said.

Priests and brokers

Christian clergy leaders receive money from dealers to find brides for Chinese men, said Augustine. The provincial minorities minister is Christian, himself. Many of the clergy are from the new, small churches that are growing quickly in number in Pakistan.

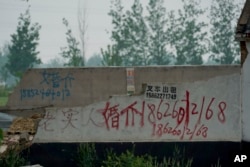

Gujranwala, a city north of Lahore, has been a special target of dealers. More than 100 local Christian women and girls have recently been married to Chinese nationals, Iqbal said.

Clergyman Munch Morris said he knows a group of pastors in his neighborhood who work with a private Chinese marriage dealer. Among them, he said, is a leader at his church who tells church members that God is happy because these Chinese boys become Christians. Morris says the leader adds, “They are helping the poor Christian girls.”

Morris opposes such marriages, calling them an insult. “We know these marriages are all for the sake of money,” he said.

Pakistani and Chinese dealers work together in the trade. One leading dealer in Gujranwala is a Pakistani known only as Robinson. He refused to talk to the AP, but his wife told the AP that they organize business a Chinese marriage bureau in Islamabad.

In China

Muqadas said her husband claimed he was wealthy. However, when she arrived in China in early December, she found herself living “in a small house, just one room and a bedroom.”

She said he rarely let her out of the house on her own. He forced her to undergo a series of medical tests. She later learned the tests were attempts to learn why she was not yet pregnant.

On the day before Christmas, when she urged him to take her to church, he hit her and broke her phone, she said.

“I don’t have the words to tell you how difficult the last month there was,” Muqadas said. “He threatened me.”

Finally, the man agreed to send Muqadas home, after her family said they would go to the police.

Denial of abuse

Muqadas and another young woman from the same neighborhood, Mahek Liaqat, said Robinson was the dealer in their marriages. Mahek’s report of her life in China was similar to Moqadas. Her husband was possessive, she said, and would not let her leave the house.

In China, her husband, Li Tao, denied abusing Mahek. He said he was a Christian and worked for a state-owned Chinese company. He said he met Mahek through a Pakistani matchmaker introduced by a Chinese friend.

Mahek’s family contacted their government for help to bring her back. Then, the police showed up at Li’s home and he said they told him he was illegally holding a woman. Mahek returned home to Pakistan.

Others, however, are unable to come back.

Mahek’s grandfather Idriis Masih said he contacted the parents of several other Pakistani girls in China who wanted to return home. All the parents were poor and he said dismissed his attempts to persuade them to work for their daughters’ return.

He said each told him, “She is married now. It is her life.”

I’m Caty Weaver. And I'm Ashley Thompson.

The Associated Press reported this story. Caty Weaver adapted it for VOA Learning English. Ashley Thompson was the editor.

Write to us in the Comments Section or on our Facebook page.

____________________________________________________________

Words in This Story

divorce - n. the ending of a marriage by a legal process

bride - n. a woman who has just married or is about to be married

greed - n. a selfish desire to have more of something (especially money)

smuggling - v. to move (someone or something) from one country into another illegally and secretly

dowry - n. money or property that a wife or wife's family gives to her husband when the wife and husband marry in some cultures

sake - n. used in phrases with for to say that something is done for a particular purpose or to achieve a particular goal or result

matchmaker - n. a person who tries to bring two people together so that they will marry each other