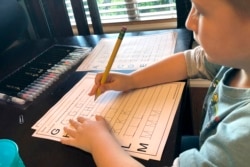

A small but growing number of Americans are choosing to homeschool their children. Most U.S. schools plan to stay closed, or open only part-time, this year and offer distance learning programs to students.

Some parents worry their neighborhood school will not offer a strong online learning program. Others are concerned about the health of their families if schools do reopen, partly or fully. Still others are choosing homeschooling because local schools keep changing their plans for the new term.

Mindy Kroesche of Lincoln, Nebraska is a writer. She had been thinking she would homeschool her 12-year-old son this year. He has autism and ADHD -- two conditions that already make middle school difficult for him.

But Mindy Kroesche always felt her 10-year-old daughter was, in her words, “built for school.” Now, with the COVID-19 health crisis continuing, she is pulling both children out for the coming school year.

“We just saw that with her wearing a mask for the entire day, that would make learning more difficult for her,” Kroesche said. “It was going to be such a different environment.”

Homeschooling applications are on the rise in several states, including Nebraska, which has had a 21 percent increase. In Vermont, applications are up 75 percent.

There were about 2.5 million homeschool students last year in levels 1 through 12 plus kindergarten. That represents 3 to 4 percent of all school-age children nationwide, reports the National Home Educators Research Institute.

Brian Ray, its president, is expecting the number of homeschool students will increase by at least 10 percent.

“One day the school district says X and four days later they say Y,” Ray said. “And then the governor says another thing and then that changes what the school district can do.”

And parents?

“They are tired of it and saying we are out of here,” he said.

Interest in homeschooling materials also has been rising. Even parents who plan to keep their children in schools are looking for ways to improve the distance learning they will receive.

The National Home School Association reports that before COVID-19 appeared, it received between five and 20 requests for information on homeschooling each day. In comparison, it received 3,400 such inquiries on a single day last month.

“Clearly the interest we have been getting has exploded,” said J. Allen Weston, the executive director of the Colorado-based group. “That is really the only way to describe it,” he added.

Some parents in rural Nebraska are turning to homeschooling because their school systems are unable to offer online learning, said Kathryn Dillow. She leads Nebraska Home Schools, a support group.

Homeschooling applications continue arriving in Nebraska, where the number of homeschoolers already had risen to 3,400 as of July 14. That is up from 2,800 at the same time a year ago, said David Jespersen, a spokesman for the Nebraska Department of Education.

Jespersen said there is “a lot of confusion” and that “parents are delayed in making their decision” because so much is changing.

He expects homeschoolers will remain a small part of about 326,000 students across the state’s 244 school systems.

Most states do not have homeschooling numbers, either because they do not collect them or they have yet to get a final count. But all signs point to increases across the country.

In Missouri, calls and emails to the homeschool group Families For Home Education increase every time a district releases its reopening plan, said Charyti Jackson, the group’s leader. She said families are in a “panic” about plans for the new school year.

“They are asking, ’What am I supposed to be doing with my children when I am working full time?’” she said.

Some families only plan to homeschool for a term or two, some in small groups. Jackson's advice to them centers on how to make sure students can transition back to public schooling easily when the pandemic ends.

There are also some signs the move to homeschooling could continue well into fall. Christina Rothermel-Branham is a psychology professor at Northeastern State University in Oklahoma.

Her six-year old son is to start the new school term online through public school. But Rothermel-Branham said the district’s program in the spring was “very monotonous.” She will change to homeschooling, she said, if the first month of public school goes poorly.

I’m Caty Weaver.

The Associated Press reported this story. Caty Weaver adapted it for VOA Learning English. George Grow was the editor.

________________________________________________________________

Words in This Story

mask – n. a protective covering for the face to designed prevent passage of infection from one person to another

application – n. a document that is used to make a formal request for something

kindergarten – n. a school or class for very young children

district – n. an area established by a government for official government business

confusion – n. a situation in which people are unsure about what to do or are unable to understand something clearly

panic – n. a state or feeling of extreme fear that makes someone unable to act or think normally

transition – n. a change from one state or condition to another

monotonous – adj. used to describe something that is uninteresting because it is always the same

We want to hear from you. Write to us in the Comments section, and visit our Facebook page.