Flerentin Jean-Baptiste missed school so often that he had to repeat his first year at Medford High School near Boston.

Jean-Baptiste said, at school, "You do the same thing every day." He was absent 30 days in his first year.

Then the principal of the school did something different: She let students play organized sports during lunch — if they attended all their classes. In other words, she offered high school students a play period that is usually part of the school day for young children.

"It gave me something to look forward to," said 16-year-old Jean-Baptiste. The following year, he cut his absences in half. Schoolwide, the share of regularly absent students dropped from 35 percent in March 2023 to 23 percent in March 2024. That was one of the biggest reductions among Massachusetts high schools.

The Associated Press and Stanford University economist Thomas Dee have studied attendance numbers from 42 states and Washington, D.C. They found that years after the school closings from the COVID-19 pandemic, schools in nearly every state are still struggling with attendance.

About one in four students in the 2022-23 school year were chronically absent. That means they missed at least 10 percent of the school year. That number represents about 12 million children in states reporting numbers of absent students.

Before the pandemic, only 15 percent of students missed school that often.

After spending as much as a year at home during the pandemic, many children see school as more than they can handle, uninteresting or socially stressful. Some children and parents are deciding it is no problem to stay home. That makes completing class work even harder.

In all but one state, Arkansas, absence rates remain higher than they were before the pandemic. Still, the problem appears to have passed its highest point; almost every state saw absenteeism go down at least a little during the two full school years ending in 2023.

Schools are trying to identify students with attendance problems so they can help. They are also trying to communicate better with parents. Some parents might not know their child is missing a lot of school or its effects on their performance.

Experts say schools must get creative to meet their students' needs.

Pay money or care about students

In Oakland, California, chronic absenteeism in public schools sharply rose from 29 percent before the pandemic to 53 percent during the 2022-23 school year. Officials asked students what would make them want to come to class. They answered, money and a mentor.

In spring 2023, the Oakland school district received a grant to pay 45 students $50 weekly to attend school every day. Sixty percent of those in the program improved their attendance. Zaia Vera is the district's head of social-emotional learning. Vera said paying students cannot continue for a long time, but many absent students lacked dependable housing or were helping to support their families. "The money is the hook that got them in the door."

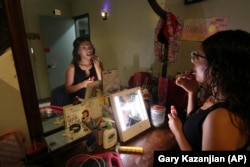

A caring teacher made a difference for 18-year-old Golden Tachiquin. She completed her studies at Oakland's Skyline High School this spring. Coming back to school after the pandemic, she felt lost and anxious. She later realized these feelings made her feel physically sick. She was absent at least 25 days that year.

One Afro-Latina teacher seemed to understand her culturally and made Tachiquin feel she belonged in class. Tachiquin already received good grades.

In Massachusetts, Medford High School requires administrators to welcome and talk with students each morning, especially those who miss a lot of class.

But playtime at lunch has had the greatest effect on improved attendance, Principal Marta Cabral said. High school students need freedom and a chance to move their bodies, she said. "They're here for seven hours a day. They should have a little fun."

Long-term problems

Many of the reasons given for students missing school early in the pandemic are still in place. They include financial difficulty, transportation problems, mild illness and mental health struggles.

For example, a study from the University of Southern California said parents reported that almost one fourth of chronically absent students had emotional or behavioral problems, compared with just seven percent of those with good attendance.

At Fresno's Fort Miller Middle School, half of the students were chronically absent. Two reasons kept coming up: dirty clothing and no transportation. The school bought a washer and dryer for families to use. It also provided a vehicle to pick up students who missed the bus. Fresno's chronic absenteeism improved to 35 percent during the school year ending in 2023.

Fourteen-year-old Melinda Gonzalez missed the school bus about once a week. So, she called for rides from the school vehicle.

"I don't have a car; my parents couldn't drive me to school," Gonzalez said. "Getting that ride made a big difference."

I’m Mario Ritter, Jr.

And I’m Jill Robbins.

Jocelyn Gecker, Bianca Vázquez Toness and Sharon Lurye reported this story for the Associated Press. Jill Robbins adapted it for Learning English.

______________________________________________

Words in This Story

absent – adj. not present at a usual or expected place

chronically – adv. in a way that is continuing or occurring again and again for a long time

stressful – adj. making you feel worried or anxious

mentor – n. someone who teaches or gives help and advice to a less experienced and often younger person

grant –n. an amount of money from a government or organization meant for a specific purpose and which does not have to be repaid

hook – n. something (such as part of a song) that attracts people's attention

anxious – adj. afraid or nervous especially about what may happen

What do you think of this story? Write to us in the Comments Section.

Forum