A Chinese scientist claims he successfully created the world’s first genetically-edited babies.

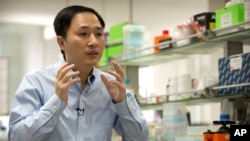

Chinese researcher He Jiankui made the claim in interviews with the Associated Press. He also spoke about his research with organizers of an international conference on gene editing in Hong Kong, the AP reported.

He is a research professor at China’s Southern University of Science and Technology in the southern city of Shenzhen.

He said he had edited the genetic substance, or DNA, of twin girls born a few weeks ago. There was no independent confirmation of He’s work and he did not provide written documentation of his research. Many scientists working in genetics say they believe such experimentation is dangerous.

He’s claims were immediately condemned by some scientists as unsafe and unethical. This kind of gene editing is banned in the United States and many other countries. Such changes to a person’s DNA can pass to future generations and risks harming other genes.

In interviews, He Jiankui defended his work. He said he had performed the gene editing to help protect the babies from future infection of HIV, the virus responsible for the disease AIDS. He said the process had “worked safely” and the twin girls were “as healthy as any other babies.”

He told the AP he felt a strong responsibility “not just to make a first, but also to make an example” for future research. “Society will decide what to do next,” he said.

China to investigate He’s activity

He had studied in the past at Rice and Stanford universities in the United States. He then returned to his homeland China to open a laboratory at Southern University of Science and Technology.

When He’s claims became public, the university issued a statement saying his work had “seriously violated academic ethics and standards.” University officials said they had no knowledge of his research and had launched an investigation. A university spokesman said the professor had been on a break from teaching since early this year. But he remains an employee and still works in the laboratory.

China’s National Health Commission said it was “highly concerned” about the claims and ordered local health officials “to immediately investigate” He’s activity. “We have to be responsible for the people’s health and will act on this according to the law,” the commission said in a statement.

Limited use of gene-editing

Scientists discovered in recent years a new way to edit genes that make up a person’s DNA throughout the body. The tool, called CRISPR-cas9, makes it possible to change DNA to supply a needed gene or take one away that is causing problems.

So far the tool has only been used on adults to treat deadly diseases, and the changes only affected that person. Editing sperm, eggs or embryos is different because such changes can be passed down. In the U.S., the process is only permitted for lab research. China bans human cloning, but not specifically gene editing.

Kiran Musunuru is a University of Pennsylvania gene editing expert and editor of a genetics journal. He told the Associated Press that if such an experiment had been carried out on human beings, it could not be “morally or ethically defensible.”

Julian Savulescu, a medical ethics expert at Britain’s University of Oxford, agreed. “If true, this experiment is monstrous,” he told Reuters.

However, one well-known geneticist, Harvard University’s George Church, defended the attempt to edit genes to prevent infections of HIV. He told the AP that since HIV is “a major and growing public health threat” he finds such experiments “justifiable.”

I’m Anna Mateo.

Bryan Lynn wrote this story for VOA Learning English, based on reports by the Associated Press, Reuters and Agence France-Presse. Hai Do was the editor.

We want to hear from you. Write to us in the Comments section, and visit our Facebook page.

_____________________________________________________________

Words in This Story

unethical – adj.morally bad

standard – n.level of quality considered acceptable

sperm – n.male reproductive fluid

clone – v.an exact copy of a plant or animal made by scientists removing one of its cells

justifiable – adj.having a good reason

We want to hear from you. Write to us in the Comments section, and visit our Facebook page.