A list of food to go. Directions for attending a funeral. A note to cancel local summer celebrations.

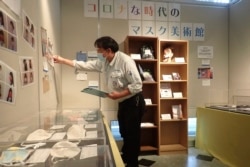

These simple, everyday objects of life in the pandemic have found a home in the Historical Museum of Urahoro in Hokkaido, in northern Japan.

This small town of 4,500 people does not even have a movie theater. But thanks to Makoto Mochida, it now has a place to tell future generations what it was like to live in the time of COVID-19, things like social distancing or public fears over the pandemic.

As curator, Makoto Mochida selects the objects to place in the museum. “I am fascinated by how things connect with people,” he said.

Mochida said some people are surprised that he is collecting objects that should be thrown away. But he believes the items provide “an excellent way to accurately archive history.” And he admits that he has problems throwing things away at home, too.

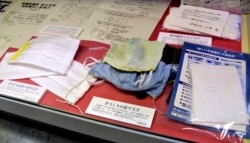

There are documents showing how children were taught to start online schooling and directions on how to make face coverings. Several hundred objects have been collected so far, after a call went out to locals in the area.

After the Spanish flu of 1918-19 – the last great world pandemic - letters and notes provided details about life during that health crisis. That pandemic killed more than 50 million people.

But these days, papers and notes have all but disappeared. And their digital versions, like emails and social media messages, are all but lost in a sea of cyberspace, Mochida said.

He is planning a big show next February to present more of his collection. It will be a follow-up to the smaller museum, which centers mainly on how masks have developed over a short period of time.

At first, masks were hard to find in Japanese stores. Some earlier ones were made by hand from old clothes. Then came masks that permit wearers to eat and drink or that were made out of clear plastics. The coverings eventually became fashion statements, some with complex designs.

Cases of COVID-19 have been growing in Japan. But Urahoro has not yet recorded a single case.

At first, the community ignored the pandemic. Then fears began to grow as outsiders and adult children working in Tokyo or nearby cities would come to visit.

The small town decided to end in-person eating at restaurants in an effort to reduce any virus spread. So people began to take out a local food favorite called “spa-cut” to eat at home. It is a meat-sauce noodle topped with fried pork. Before the pandemic, it was not even a possibility to take the popular food home.

Shoko Maede was born in Urahoro and works as a cook at a school for young children. She says that many years from now she can almost imagine how people will struggle to remember what life was like during the pandemic.

“They may think, ‘Oh, so this was the way it was,’” she said, after visiting the museum.

I'm Bryan Lynn.

Yuri Kageyama reported this story for the Associated Press. Hai Do adapted the story for Learning English. Bryan Lynn was the editor.

________________________________________________________________

Words in This Story

pandemic - n. an occurrence in which a disease spreads quickly and affects a large number of people around the world

curator - n. a person who is in charge of the things in a museum

fascinated - adj. very interested in something

accurately - adv. free from mistakes or errors

archive - v. to collect and store materials (such as recordings, documents, or computer files) so that they can be found and used when they are needed

digital - adj. using or relating to computer technology

cyberspace - n. the online world of computer networks and especially the Internet

mask - n. a covering used to protect your face or cover your mouth